After I graduated I kept track of a few of my classmates and instructors as able and learned that Frank had gone to New York City, the Big Apple, and acquired a loft somewhere in Manhattan. The last I heard he was doing a painting of a piano. A former classmate of mine had gone to see him and found that he'd been working on this painting for over a year. In order to do the painting he'd not only been doing preliminary drawings, he'd spent a great deal of time learning to play the thing, becoming intimately acquainted with not only its appearance but also its aural qualities.

This effort by Frank Holmes to become so fully immersed with the piano so as to experience the meaning of piano, this was the image that came to mind as I read David Foster Wallace's essay "Roger Federer as Religious Experience," the selection chosen to open his posthumous collection of essays assembled under the title Both Flesh and Not*.

This essay is a remarkable achievement. Here's the opening paragraph to whet your appetite:

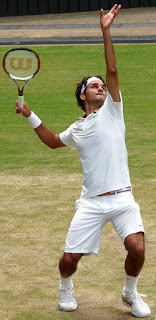

|

| CC by 2.0 |

Remarkably, reading David Foster Wallace's prose has -- for the astute reader -- the same effect. As I read this essay, in an attempt to see what all the hoopla was about this legendary author (featured in last year's superb sleeper, The End of the Tour) I come away feeling something akin to the thrill that one must have felt after witnessing a Houdini performance.

The film (End of the Tour) may have failed to fill Hollywood billfolds with greenbacks, but it did succeed in introducing a few more readers to the Wallace sensation. I was not one beforehand, so I'm admittedly late to the party.

But this all misses the point of my blog post here, and I'd best return to it quickly. The point is, Wallace is at times a magician with words, especially in this essay where he paints in excruciating detail the godlike talents displayed in this mortal tennis player, Roger Federer. What Wallace does, however, is demonstrate his own intimacy with the game of tennis, and not only tennis today but its past history, its great players of the past, its challenges in the present, and the context in which this remarkable human has come into existence. Wallace paints a picture so vivid that a photograph could not capture more detail.

One of the words he keeps returning to is the word beauty. "Beauty is not the goal of competitive sports,," he writes, "but high-level sports are a prime venue for the expression of human beauty. The relation is roughly that of courage to war."

After a great deal of setup, and a fascinating amount of detail about the ceremonial coin toss, Wallace returns to a description of Federer's beauty as a performer/player.

A top athlete’s beauty is next to impossible to describe directly. Or to evoke. Federer’s forehand is a great liquid whip, his backhand a one-hander that he can drive flat, load with topspin, or slice — the slice with such snap that the ball turns shapes in the air and skids on the grass to maybe ankle height. His serve has world-class pace and a degree of placement and variety no one else comes close to; the service motion is lithe and uneccentric, distinctive (on TV) only in a certain eel-like all-body snap at the moment of impact.

|

| Roger's signature (Public Domain) |

Mario Ancic’s first serve, for instance, often comes in around 130 m.p.h. Since it’s 78 feet from Ancic’s baseline to yours, that means it takes 0.41 seconds for his serve to reach you. This is less than the time it takes to blink quickly, twice.

And when he describes Federer's performance on this fateful day, the descriptions are themselves delightful, magical and marvelous. And it's all done with so naturally, unpretentious. There isn't a hint of the intentional showiness that Katherine Anne Porter derided when she wrote, "When virtuosity gets the upper hand of your theme, or is better than your idea, it is time to quit."

I used to do magic tricks when I was growing, card tricks and fumbling sleight of hand. It can be fun to see the befuddlement on other kids' faces when you pull something off. Bur when you see the dazzling handiwork of a master magician, making things disappear and re-appear elsewhere directly in front of your eyes, it can be breathtaking. And that's the feeling I had as I read this essay. I was watching a magician at work, just as he was describing the magician Roger Federer working to put away Nadal, his opponent.

Federer isn't the only sports superstar who appears to bend the rules of physics. Wallace cites Michael Jordan and Wayne Gretzky in a similar way. But the essay always returns to Federer, and it's my hope that you will take the time to read this wonderful piece.

Or you can go for the whole book. You'll find some excellent insights on writing, and a really superb smackdown of Hollywood's love affair with SFX, which essentially amounts to a blistering review of T-2.

Meantime, life goes on all around you. Dig it.

*EdNote: Since Both Flesh and Not is a posthumous collection I can't give GFW credit for the clever title. It's ambiguous and leaves much to the imagination. It could make sense to assume it's Flesh and Bone, with some suggestiveness attached to the latter, though as Freud famously quipped, "Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar."

The title could be completed with another common conbo, Flesh and Spirit. Wallace grew up going to Sunday School and no doubt heard the admonition to live by the Spirit and not the flesh, the two warring factions of the Self that Paul writes about in his letter to the Romans, or his warmup on the theme in his counsel to the church of Galatia.

Flesh and Blood is another possibility. This pair is also featured in many a quote from literature (eg.: “The savage bows down to idols of wood and stone, the civilized man to idols of flesh and blood” --George Bernard Show) as well as the Bible. ("Our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but principalities and powers...")

No comments:

Post a Comment