Despite waiting years for Dylan's sequel to Chronicles: Volume One, I did not order my copy of his Philosophy of Modern Song in advance last year, as I might normally have done. Rather, I requested it as a Christmas present and thus received it after weeks of reviews had already appeared. The "controversy" regarding his "autograph scandal" didn't phase me. Nor did the misogyny brickbats.

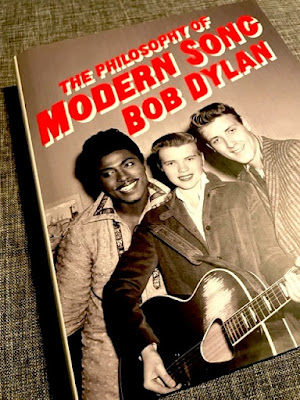

So here it is, sitting before me on the coffee table/wooden chest, beckoning me to express my initial first reactions.

* * *

The Philosophy of Modern Song is not anything like what most of us expected as the sequel to Chronicles Vol. 1. The writing, however, feels like a Dylan volume. Most Dylan fans who have listened to his Theme Time Radio show will very likely hear Dylan's voice reading it aloud as they read the text.

The book itself is a collection of essays on 66 songs by other artists, spanning from Stephen Foster to Elvis Costello. It has the look of a scrapbook in some ways. To some extent that makes sense in a pop culture sort of way. (When I was in Italy, I was talking about Dylan with a fellow who owned a craft brewery. He had a couple Dylan posters on the wall so I commented on my surprise at how much Dylan had been imported into Italy. He said, "America gave us two things: Bob Dylan and Pop Culture.")

According to the text on the inside cover flap Dylan began working on it in 2010. The sales-copy describes it as "a master class on the art and craft of songwriting," though quite a few critics demur on this proclamation.

John Carvill at PopMatters.com, for example, wrote, "There’s very little of what we could sensibly consider ‘modern song’ in The Philosophy of Modern Song, and any ‘philosophy’ is strictly of the cracker barrel variety. That’s ok, though, because we’ve learned never to take Dylan at face value, and the title was just too pretentious to have been meant seriously." The subhead to that article calls it "an awful book, awash with misogyny and crusty old man rants."

I found that last barb to me a little harsh, but having become an older man myself I do understand why folk become "crusty" in their later years.

I found that last barb to me a little harsh, but having become an older man myself I do understand why folk become "crusty" in their later years.

(4columns)

On the other hand, if you're seeking reviews with a little more enthusiasm for the subject matter (Bob's sequel to Chronicles: Volume One) then here's the place to be: 130+ Published Reviews of Dylan's Book.

I believe I did see at least one reviewer agree it that was "master class on the art and craft of songwriting." I saw it as something different.

I enjoyed seeing the variety of songwriters selected. No surprise to find spotlights on Elvis, Little Richard, Johnny Cash and Hank Williams, as long-time fans know his respect for the music of these giants. Happy surprises include Stephen Foster, Nina Simone and many others. As for Dylan's impressions on pop hits from my own Boomer-era lifetime, there were many, such as "Ball of Confusion" by the Temptations, "Black Magic Woman" by Santana, "By the Time I Get to Phoenix" by Jimmy Webb, etc. And then there are all the slices and slivers from other assorted musical genres that you probably would not have expected.

The writing style is, as I noted, more of a rhythmic impressionism, a Dylan style you find in songs like "Subterranean Homesick Blues," punchy phrases falling all around like shrapnel from a hand grenade.

Here's an excerpt from his chapter on Cher's "Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves" which is accompanied by old photos of a Peep Show carnival barker and a Side Show Zoo sign.

You've evolved over thousands of years and you're still traveling through, setting up the tent and making ends meet. Hoaxes, tournaments and spectacles, that's your line of business. Drugstore cowboys, girl watchers, night owls--everybody and their uncle, you lighten them up and bleed them with ease. You give nightmares to people while they're fully awake. People whisper behind your back--lampoon you, satirize, mock and ridicule you, make bitchy comments but your place in the sun is secure.

Here's a digression from another chapter.

You're in an exclusive club, and you're advertising yourself. You're blabbing about your age group, of which you're a high-ranking member. You can't conceal your conceit, and you're snobbish and snooty about it. You're not trying to drop any big bombshell or cause a scandal, you're just waving a flag, and you don't want anyone to comprehend what you're saying or embrace it, or even try to take it all in. You're looking down your nose at society and you have no use for it. You're hoping to croak before senility sets in. You don't want to be ancient and decrepit, no thank you. I'll kick the bucket before that happens. You're looking at the world mortified by the hopelessness of it all.

In reality, you're an eighty-year-old man, being wheeled around in a home for the elderly, and the nurses are getting on your nerves. You say why don't you all just fade away. You're in your second childhood, can't get a word out without stumbling and dribbling. You haven't any aspirations to live in a fool's paradise, you're not looking forward to that, and you've got your finger....

In the first paragraph you are you, in a hopeless world. But suddenly, you are an eighty-year old man in a home for the elderly. Is that a pivot? Is Dylan saying what he means or is it the opposite? Is this his take on the sunset years?

MY TAKE

Philosophy of Modern Song is fun, but is best enjoyed if you treat it like a book of poetry next to your easy chair which you can dip into and savor any time of day or night. Don't take it too seriously. Just enjoy it.

Related Links

Bob Dylan In Italy

What Does Charles Trenet's "La Mer" Have to Do with Dylan's Philosophy of Song?

Postscript

"an enthralling farrago of fabrications and tangents that occasionally, when it circles back to his early life on the Greenwich Village folk scene, offers rare bits of vivid personal disclosure, including meditations on artists and songs that helped shape him."

--Bob Dylan, Philosophy of Modern Song

Illustration Credit: Collaboration with Dream by Wumbo.

Photo credits: the author, the latter at the train station in Florence, Italy.

2 comments:

What to make of the book as a whole, to those voices we’re hearing? Trying to square the book’s wiser moments with its wilder, noirish riffs, while the misogynistic ravings of King Lear on the heath come horribly to mind – something a few critics have made much of - so too does, for me, and perhaps rather improbably, TS Eliot. The original title of, The Waste Land, was, quoting Dickens – and the reference is to a character who’s a brilliant mimic – ‘He do the police in different voices’. Doing ‘different voices’ is something we’ve met in Dylan for decades, quite literally in the singing voice, but more interestingly in the range of personas he’s adopted or entered.

The Philosophy of Modern Song, not unlike Eliot’s poem (particularly in its much longer draft form) presents us with a variety of ‘voices’, from the quietly profound to the shockingly violent, from the deeply informed to the near-disturbed.

A striking feature of the wilder passages is Dylan’s use of the second person pronoun. What he’s doing each time is ventriloquizing - addressing his ‘Pump It Up’ narrator, for example, vividly imagining and enacting the rage and heartbreak behind the song’s aggression - while on ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ he’s elaborating, hyperbolizing, making the song his own.

Talking about old age, say, or contemporary culture, or, most importantly, music, Dylan talks with authority and authenticity. When he adopts that second person he’s addressing the song, addressing its narrator or voice and we need to remind ourselves that it’s an act of reclamation, an act of recreation.

When Shakespeare puts racist language into Iago’s mouth we don’t, unless we’re sadly naïve, assume that Shakespeare was racist. When Dylan imagines himself into the lurid world of those ‘you’s he addresses he articulates and becomes that ‘you’ in, again, sometimes shockingly particularised terms. It’s a kind of hallucinatory hyper-reality, doing ‘different voices’. Just as, he tells us in a recent song, he’s like Anne Frank or a Rolling Stone, ‘ a man of contradictions …a man of many moods’, in this sometimes dazzling, sometimes diverting, often disorientating (and wonderfully illustrated) book, he speaks, like the inhabitants of Eliot’s Waste Land, in many tongues.

Great insights. Thanks for making time to lay it out there.

e.

Post a Comment